To hear historian and author Russell Magnaghi describe it, the UP was home to Fusion Cuisine more than 200 years before the trendy term was coined.

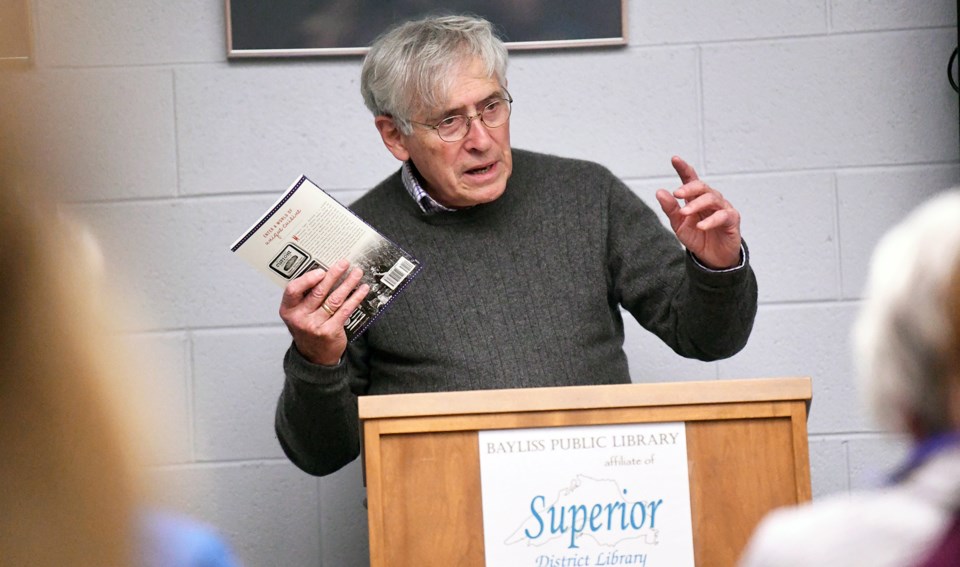

Magnaghi was at Bayliss library Tuesday evening discussing his new book, Classic Food and Restaurants of the Upper Peninsula. And while it isn’t surprising the UP has settled on what Magnaghi calls the UP Trio – pasties, cudighi sausage, and Mackinac fudge – it is the story of how immigrant and native food traditions made fusion cuisine not trendy, but a necessity.

“I see an amalgam of European farming culture and native hunting culture,” said Magnaghi. “European immigrants to the UP largely came from a farming background who found themselves in a climate that didn’t necessarily support it. More and more they tied into the native culture of hunting wild game to supplement domestic livestock.”

The cultural blend sometimes had interesting results. Take a dinner held in Ontonagon that celebrated the Scottish holiday of St. Andrews Day, on Nov. 30, 1855.

“A newspaper article mentions the expected turkey, mutton, scones and haggis,” Magnaghi said. “But the menu also lists beaver tail, caribou, buffalo rump roast, whitefish steaks, broiled siskiwit (Lake trout), and my favorite, porcupine à la Ontonagon. Most of what was served that night to commemorate an Old-World holiday was regional wild game.”

Magnaghi’s food research also illuminated lingering misconceptions about how Native Americans tapped regional fruits and vegetables.

“Many people confuse the term ‘gathering’ with just going out when you feel like it and collecting what is there,” he said. “But Natives had an awareness for seasonal variety, where certain foods grew under what conditions and when. Collection was highly organized and optimized not only for themselves, but for trade.”

Magnaghi offered sugar-maple sap harvesting as an example.

“Natives collected sap on a massive scale hundreds of years before Europeans arrived,” he said. “They boiled it down past syrup into something more storable and transportable – maple sugar.”

It takes 40 gallons of sap to produce one gallon of syrup, so producing an even more concentrated sugar requires more time – and sap.

“Natives tapped and reduced maple sap on a scale that echoes operations we see today,” Magnaghi said. “Records say that in 1800, area tribes sold two tons of sugar to federal Indian agents, and this is above what they produced for themselves.”

Magnaghi maintains that this practice goes into a realm of managed harvesting, the foundation of agriculture.

Managed abundance was also practiced by UP immigrants, Magnaghi said.

“There was a huge apple culture in Chippewa county,” he pointed out. “You’ll find abandoned apple trees everywhere, and in yards of older homes. Six varieties of apples ripened between June and late fall. A late apple was harvested in November and held in a cellar to ripen slowly. So, people could enjoy fresh apples into March . . . eight weeks before the cycle starts over.”

Magnaghi discussed another forgotten UP crop, celery.

“For 80 years, starting the 1880s, Newberry was known as Michigan’s celery capital,” he said. “Stalks were shipped throughout the region touted as Newberry celery. Newberry’s athletic teams were known as the Celery City Cagers and the Celeryettes.”

Eventually celery production moved to California, along with growing of much of the country’s produce, in the middle part of the 20th Century. Newberry’s celery days were extinct by the 1960s.

The EUP also was also home to the country’s first large-scale canning of jams, as Magnaghi related.

“Philetus Church set up a fueling station for passenger boats on Sugar Island, so they could load up with wood just before or after the Locks,” he said. “Among the curios and foodstuffs, he sold raspberry preserves in sealed jars. Word about jam got back to cities and by 1878 he was selling 12 tons of it every year. All of it was harvested from the wild by local tribes.”

Another EUP culinary innovation ties directly into Magnaghi’s next book project about African Americans in the UP.

“As early as the 1850s, most of the Grand Hotel’s cooking and service staff were escaped slaves from the South,” he said. “This trained workforce of black cooks, waiters, and stewards expanded onto steamers that shuttled people and goods all over the Great Lakes. The Pullman Car Company built and operated passenger cars for the nation’s railroads tapping this workforce as well.”

For other UP food-related stories, from the last of the drive-ins to UP winter wheat, running the gamut from world-record pasties to the origin story of cudighi, purchase a copy of Classic Food and Restaurants of the Upper Peninsula wherever books are sold.